An interview with James Kippen

➡ Version française

by Antoine Bourgeau

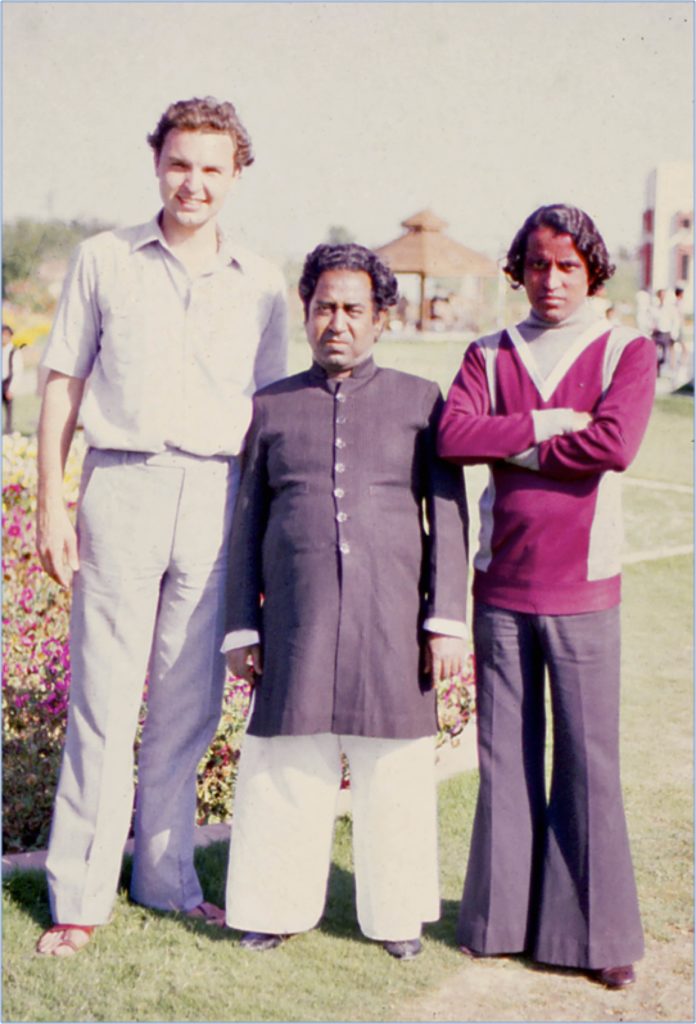

James Kippen is one of the key figures in the study of Hindustani music. His encounter in 1981 with Afaq Hussain, at the time the doyen of one of the great tablā-playing lineages, was the starting point for major research into both the instrument and Indian rhythm. From 1990 to 2019 he was the head of ethnomusicology at the Faculty of Music in the University of Toronto in Canada. Trained under John Blacking and John Baily, he also acquired over the course of his research a mastery of several Indo-Persian languages. This ability has allowed him to analyse first-hand numerous sources (treatises on music, musicians' own writings, genealogies, iconographic materials…) and to understand the changing sociocultural contexts in which they were produced (the Indo-Persian courts, the colonial British Empire, the rise of Indian Nationalism, and the post-colonial state). His work (see the select list of publications at the end of this interview) stands out as a major contribution to the understanding of the theory and practice of rhythm and metre in India.

I began corresponding with James Kippen during my own research on tablā at the end of the 1990s. Always quick to share his knowledge and his experience with enthusiasm, he gave me a lot of advice and encouragement, and it was a great honour to count him among the members of my thesis jury during my defence in 2004. It was with that same willingness to share that he responded favourably to my proposal to interview him. Carried out remotely between July and December 2020, this exchange covers nearly 40 years of ethnomusicological research.

➡ Source = doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.12650.03522

➡ Version française = doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.26071.80804

ou https://bolprocessor.org/kippen-interview-fr/

The path to India and to the tablā

– How did you become interested in the musics of India, and in the tablā in particular?

As a child growing up in London, I was fascinated by the different languages and cultures that were increasingly being introduced by immigrants to Britain. I was particularly enchanted by the little Indian corner shops brimming with exotic goods and the Indian restaurants that emitted alluring, spicy aromas. My father regularly regaled me with stories of his adventures from the seven years he spent in India as a young soldier, and I developed an entirely favourable though admittedly Orientalist impression of the subcontinent. During my music degree at the University of York (1975-78), I was introduced by my friend and fellow student Francis Silkstone to the sitār. I also had the good fortune to take an intensive course in Hindustani music with lecturer Neil Sorrell, who had studied sāraṅgī with the great Ram Narayan. The available literature at that time was relatively sparse, but two texts in particular were highly influential: Rebecca Stewart's Tablā in Perspective (UCLA, 1974), which nurtured in me a musicological interest in the varieties and complexities of rhythm and drumming, and Daniel Neuman's The Cultural Structure and Social Organization of Musicians in India: the Perspective from Delhi (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, 1974), which offered social-anthropological insights into both the worlds and the worldviews of traditional, hereditary musicians.

Thus, I began learning tablā from Robert Gottlieb's LP recordings and booklets called 42 Lessons for Tabla, and after a few months I had learnt enough basic material to accompany Francis Silkstone in a recital. I later studied in person under Manikrao Popatkar, an excellent professional tablā player who had recently immigrated to Britain. I was hooked. Moreover, the thought that I might enter that socio-musical world of tablā in India and become a participant-observer motivated me to look at graduate programs where I would be able to develop the knowledge and skills to combine the musicological and anthropological approaches of Stewart and Neuman. On Neil Sorrell's advice I wrote to John Blacking about the possibility of studying at The Queen's University of Belfast, and John was most encouraging, offering me entry directly to the doctoral program. He also pointed out that his colleague John Baily had recently written a text: Krishna Govinda's Rudiments of Tabla Playing. It seemed I had found the ideal graduate program and the perfect mentors.

Methodological approaches

– The book How Musical Is Man? by John Blacking is a fundamental text that appeared in 1973 that ran counter to the thinking of the time and refused to recognise the barriers between musicology and ethnomusicology, as well as the fruitless differences between musical traditions. Blacking also put forward the essential idea that music, even if that word does not exist everywhere, is present in all human cultures, resulting in his definition of “humanly organised sound.” Do you know if he knew of Edgar Varèse's expression “organised sound,” which Varèse put forward in 1941 in an attempt to distance himself from the Western concept of “music,” albeit for other reasons?

I have no personal recollection of Blacking ever mentioning Varèse or his thoughts on the nature of music. Nonetheless, Blacking was an excellent musician and pianist who had doubtless encountered and studied a great deal of Western Art Music, and so it is possible he knew of Varèse's definition. However, whereas Varèse's philosophy was born out of a conviction that machines and technologies would be capable of organising sound, Blacking wanted to re-centre music as a social fact: an activity where the myriad ways in which human beings organised sound both as performers and, importantly, as listeners promised to reveal a great deal about their social structure.

– How did your studies at university guide your research?

I was lucky enough to have not one but two mentors in John Blacking and John Baily, and they were very different from one another. Blacking was full of grand and inspiring ideas that challenged and revolutionized the way one thinks about music and society, whereas Baily emphasized a more methodical and empirically-based approach grounded in performance and the careful acquisition and documentation of data. One should remember that I was young and inexperienced when I undertook fieldwork, and so Baily's example, focussed on doing music and on gathering data, served as a practical guide in my daily life during my years in India; yet once I was armed with a huge corpus of information I was able to stand back and, hopefully like Blacking, see some of the grand patterns which that data spelled out. I was struck therefore by the consistent narrative of cultural decline linked to a nostalgia for a glorious and artistically-abundant past, and the tablā music of Lucknow was one of the last living links to that lost world. This became one of the key themes in my doctoral dissertation, and in some of the other work that followed. As for my career as a teacher, I have tried over the years to combine the best qualities of both my mentors, always promoting the idea that theory should grow out of solid data about music and musical lives so that it does not lose its heuristic value by abandoning its dialogue with ethnographic reality.

– In Working with the Masters (2008), you describe in detail and with frankness (something that is fairly rare in the profession!) your fieldwork experience with Afaq Hussain in the 1980s. This experience, and your account of it, appear to be a model for any research in ethnology and ethnomusicology, particularly as it applies to learning music. Thus, you account for the phases of approaching, meeting, being tested and, finally (and fortunately in your case), acceptance within the research context; the trust you were granted allowed you to pursue in full your research and music-learning goals. You also tackle the ethical and deontological considerations essential to any researcher: one's relationship to others, conflicts of loyalty resulting from possible inconsistencies between that relationship and one's ethnographic objectives, responsibility to the gathered knowledge, and the place of the researcher-musician within the musical reality of the tradition studied. Beyond the particularities of the musical context, are there any specific features of Indian culture that Western researchers need to bear in mind in order to undertake (and hopefully succeed with) an ethnological study in India?

It goes without saying that South Asian society has changed enormously in the 40 years since I first began conducting ethnographic research, but certain principles steadfastly remain that should guide the investigative process, such as a deeply ingrained respect for social and cultural seniority. Naturally, access to a community is key, and there is no better “gatekeeper” or “sponsor” (to use the anthropological terms) than an authority figure within the subculture one is studying, since the permission one receives trickles down through the social and familial hierarchy. The danger, in a heavily patriarchal society like India's, is that one ends up with a top-down view of musical life. If I had an opportunity to revisit my field I would pay greater attention to those at different levels within that hierarchy, especially to women and to the everyday musicality of life in the domestic sphere. By focussing only on the most refined aspects of cultural production, one may miss much that is of value in the formation of ideas, of aesthetics, and in the support mechanisms necessary for an artistic tradition to survive and thrive.

On a more practical note – something that applies I think rather more generally in the fieldwork endeavour – I found that formal, recorded interviews were rarely very insightful because they were felt to be intimidating and were accompanied by lofty expectations. Furthermore, a heightened sensitivity to the political ramifications – micro and macro – of speaking one's mind on record was also often an impediment to gathering information. In truth, the less I asked and the more I listened – off the record and in relaxed circumstances – the more useful and insightful the information I received. The caveat is that to operate in that way one must develop a level of patience that would be difficult for most Westerners to accept.

– In the 1980s you adopted the “dialectical approach” taught by John Blacking and combined it with computer science and an Artificial Intelligence program. The aim was to analyse the fundamentals of improvisation by tablā players. Can you go over the genesis and evolution of this approach?

John Blacking was particularly interested in Noam Chomsky's work on transformational grammars. He theorized that one could create sets of rules for music – a grammar – with the topmost layer describing how those surface sound structures were organised. At deeper levels the layers of rules would address increasingly more general principles of musical organisation, and at the very deepest level the grammar would formalise rules governing principles of social organisation. If an ethnomusicologist's ultimate aim is to relate social structure to sound structure, or vice versa, then this was Blacking's idea of how one might achieve that goal.

In the summer of 1981, I escaped the intense heat of the North Indian plains and headed to Mussoorie in the foothills of the Himalayas. I had agreed to meet up again with my friend Francis Silkstone, who at the time was studying sitār with Imrat Khan and dhrupad vocal music with Fahimuddin Dagar in Calcutta. Francis arrived with Fahimuddin and one of Fahim's American students named Jim Arnold. Jim was collaborating on some experimental work on rāga intonation with Bernard Bel, who at that time was living in New Delhi. Bernard then arrived in Mussoorie, also to escape the heat, and for about a month we all lived together in a rich and fertile environment of music and ideas. It was there that Bernard and I first discussed Blacking's notion of socio-musical grammars as well as my fascination with tablā's theme-and-variations structures known as qāida. I was intrigued when Bernard suggested that he could design a computer program capable of modelling the process of creating variations from a given theme.

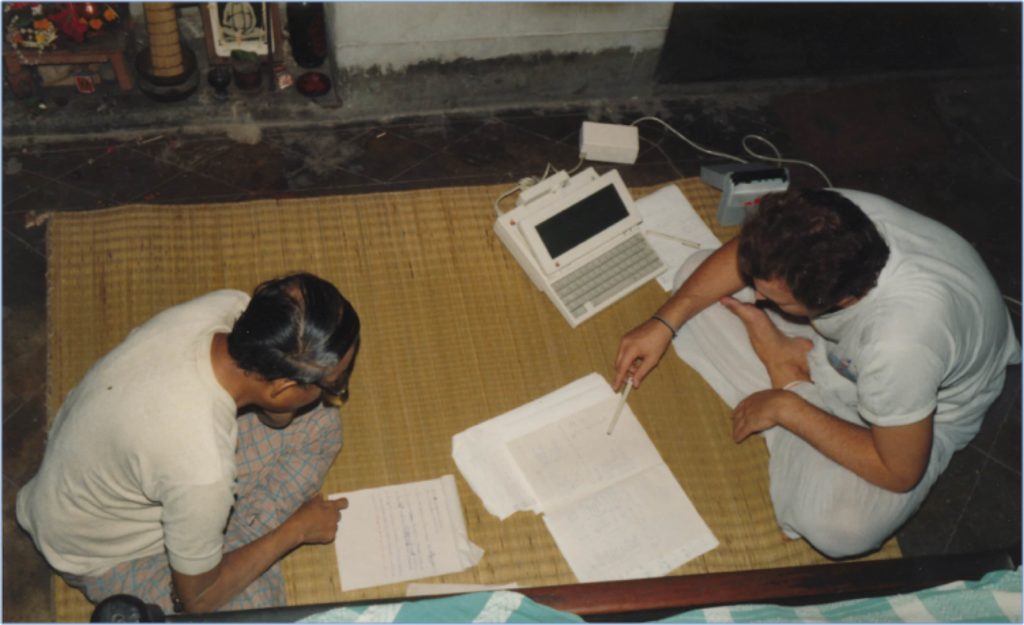

Over the following year, Bernard and I met several times: he learnt much more about how tablā works and I learnt much more about mathematical linguistics. Together we created sets of rules – transformational grammars – that generated variations from a qāida theme and processed existing variations to determine if our rules could account for them. Yet it was also clear that the knowledge being modelled was my own and not that of expert musicians. Therefore, we developed a strategy to involve those experts as “co-workers and analysts” (a phrase Blacking often used) in a dialectical exchange. After all, an “expert system” was intended to model expert knowledge, and there was no better expert than Afaq Hussain.

➡ For more information about these experiments, visit: https://bolprocessor.org/bp1-in-real-musical-context/

– Were you aware of other types of interactive approaches, such as Simha Arom's “re-recording” developed a few years earlier?

I was aware of Simha Arom's interactive methods of eliciting musicians' own perspectives on what was happening in their music, much as I was aware of work in cognitive anthropology aimed at determining cognitive categories meaningful to the people we studied. Arom's insistence that cultural data had to be validated by our interlocutors was certainly very influential. I did not know of other approaches. The exigencies of our particular experimental situation forced us to invent our own unique methodology for this human-computer interaction.

– We know of the fear Indian masters have of their knowledge being spread beyond their own gharānā, in particular, certain techniques and compositions. What was Afaq Hussain's attitude regarding this, and what was his involvement in this method that updated the software for examining qāida structures?

Afaq Hussain was not remotely concerned about revelations regarding qāida since the art of playing them depended on one's ability to improvise. In other words, this was a process-oriented and therefore ever-changing endeavour. On the contrary, playing fixed compositions, especially those handed down over generations within the family, were product-oriented, and the pieces did not change. Those were considered precious assets, and were carefully guarded.

Hussain. Lucknow, 1982. Photo by James Kippen.

When I reflect on the experiments, I marvel that Bernard Bel was able to create such a powerful generative grammar for a computer (firstly an Apple II with 64k RAM, then the portable 128k Apple IIc) with such limited processing power and space. Afaq Hussain also marvelled that a machine could “think,” as he put it. We began with a basic grammar for a given qāida, generated some variations, and I then read those out loud using the syllabic language, the bols, for tablā. Many results were predictable, some were unusual but nonetheless acceptable, and others were deemed to be wrong – technically, aesthetically. We then asked Afaq Hussain to offer a few variations of his own; these were fed into the computer (I typed using a key-correlation system for rapid entry) and “analysed” to determine if the rules of our grammar could account for them. Simple adjustments to the rules were possible in situ, but when more complex reprogramming was required we would move on to a second example and return to the original example in a later session.

– Did this research ever involve other types of composition such as gat or ṭukṛā?

No. The advantage of looking at a theme-and-variations structure like qāida is that each composition is a closed system where variations (vistār) are restricted to the material presented in the theme. Relā (rapidly-articulated strings of strokes) is another structure that follows similar principles. The aim is therefore to understand the unwritten rules for creating variations. Fixed compositions such as gat, ṭukṛā, paran, etc., comprise a far wider and more unpredictable variety of elements, and would be very hard to model. However, one thing we did experiment with was the tihāī, the thrice-repeated phrase that acts as a final rhythmic cadence. These can be modelled mathematically and applied to a qāida (based on fragments of its theme or one of its variations) or to fixed compositions like, say, ṭukṛā as an arithmetic formula into which one can pour rhythmic phrases.

– Did any of the rhythmic phrases generated by the computer and validated by Afaq Hussain Khan make it into the repertoire of the Lucknow gharānā?

That is a hard question to answer. When we were in the middle of an intensive period of experimentation with the Bol Processor, there would develop a kind of dialogue where Afaq Hussain would play material generated by the computer and then respond with sets of variations of his own. So many were generated and exchanged in this way that it was often hard to tell whether something he played in concert originated in the computer. Yet, whereas some teachers and performers develop a repertoire of fixed variations for a theme, Afaq Hussain rarely did, relying instead on his imagination “in the moment.” This is also the approach he encouraged in us. Therefore, I doubt computer-generated material became a permanent part of the repertoire.

– Has this specific type of approach using Artificial Intelligence in ethnomusicology been pursued by others?

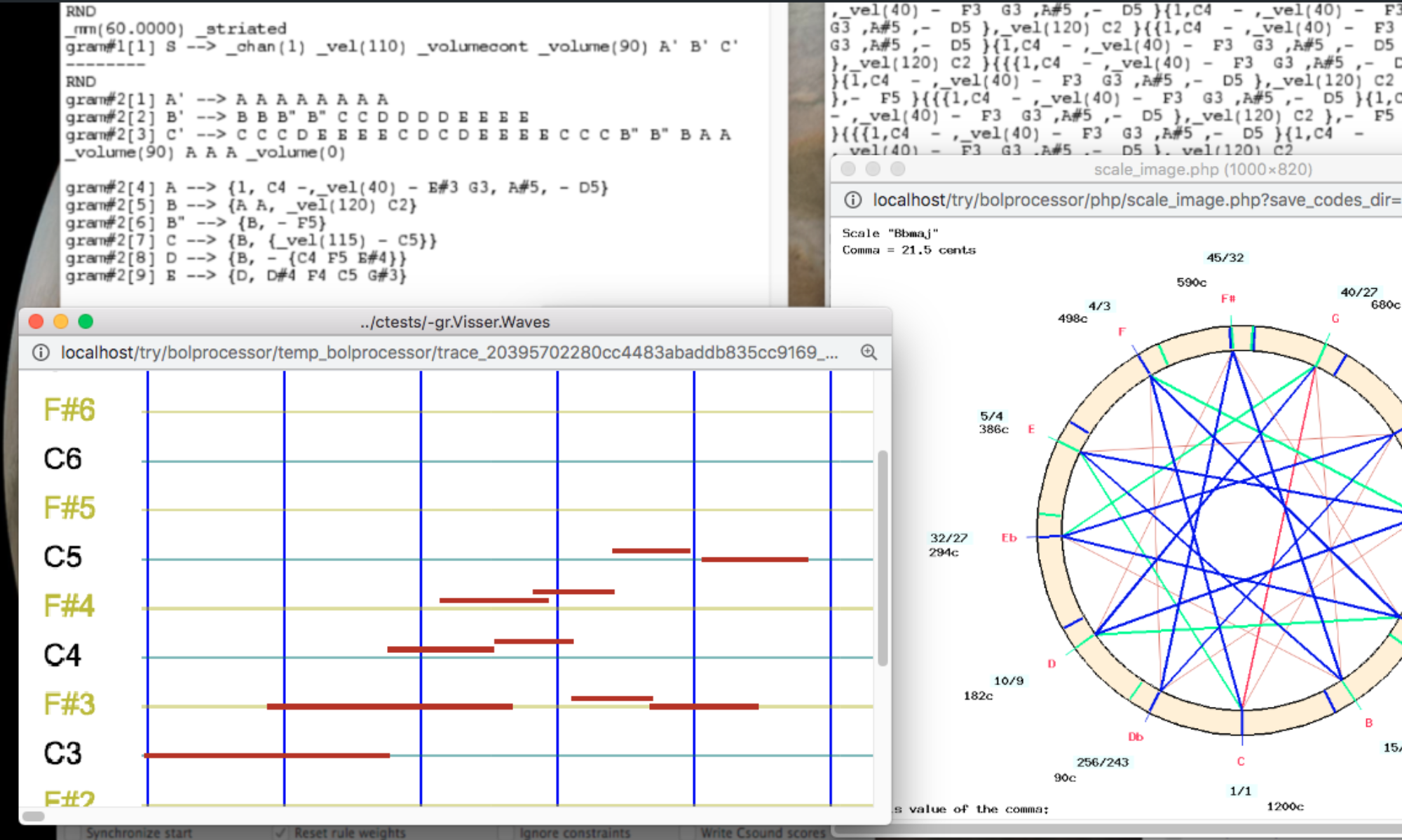

The term “Artificial Intelligence” underwent a radical change in the years 1980-1990 thanks to the development of the “connectionist” approach (artificial neurons) and learning techniques from examples with the capability of processing a large amount of data. With the Bol Processor (BP) we were at the stage of symbolic-numerical modelling of human decisions represented by formal grammars, which required in-depth, although intuitive, knowledge of decision mechanisms.

For this reason, symbolic-numerical approaches have not to my knowledge been taken up by other teams. On the other hand, we had also tackled machine learning (of formal grammars) using the QAVAID software written in Prolog II. We also showed that the machine had to collect information by dialoguing with the musician in order to carry out a correct segmentation of musical phrases and to begin generalising by inductive inference. But this work was discontinued because the machines were too slow and we did not have a large enough body of data to build a model capable of covering a wide variety of improvisation models.

It is possible that Indian researchers will use learning from examples – now called Artificial Intelligence – to process large amounts of data produced by percussionists. This “big data” approach has the drawback of lacking precision in a field where precision is a marker of musical expertise, and it does not produce understandable algorithms which would constitute a “general grammar” of improvisation on a percussion instrument. Our initial ambition was to contribute to the construction of this grammar, but we only proved, using the technology available at the time, that it would be feasible.

– In later versions, this software was also able to provide material and tools for music and dance composition beyond the Indian context. We will be celebrating 40 years of this software next year with a new version. Who are the artists that have used this software?

Rhythmic compositions programmed on BP2 and performed on a Roland D50 synthesiser were used for the choreographic work CRONOS directed by Andréine Bel and produced in 1994 at the NCPA in Bombay. See, for example, https://bolprocessor.org/shapes-in-rhythm/.

At the end of the 1990s, the Dutch composer Harm Visser used BP2 to help develop operators for serial music composition. See, for example, https://bolprocessor.org/harm-vissers-examples/.

We have had feedback (and requests) from European and American academics who use BP2 as an educational tool for teaching musical composition. However, we have never carried out a large-scale advertising campaign to enlarge the user community because we are primarily interested in the development of the system itself and in the musicological research associated with it.

The main limitation of BP2 was its exclusive operation within the Macintosh environment. This is why the BP3 version under development is cross-platform. It will probably be implemented in a Cloud version made possible by its close interaction with Csound software. This software makes it possible to program high-performance sound production algorithms and to work with microtonal intonation models that we have developed, both for harmonic music and for Indian rāga. See, for example, https://bolprocessor.org/category/related/musicology/.

Studies of notation, metre, rhythm, and their evolution

– Over the course of your work, the question of musical notation has occupied an important place both in terms of methodology and also in considerations of how it is used. Can you speak to this aspect of your work?

All written notations are incomplete approximations, and their contribution to the transmission process is limited. Oral representations, like the spoken strings of syllables representing drum strokes, often convey more accurate information about the musicality inherent in patterns, such as stress, inflection, phrasing, and micro-rhythmic variability. By the same token, once internalised, those spoken strings are indelible. We know that oral systems promote a healthy musical memory, which is particularly important in the context of the performance of music in India where performers begin with only a very general road map but then take all manner of unexpected twists and turns along the way. That being the case, one might ask why write anything down at all?

From the 1860s onwards, there was a burgeoning of musical notations in India inspired, I believe, by an awareness that Western music possessed an efficient notation system, and prompted too by the steady increase in institutionalised learning and the perceived need for pedagogical texts and associated repertoire. Yet there was never any consensus on how to notate, and each new system differed greatly from the others. The notation devised in 1903 by Gurudev Patwardhan was arguably the most detailed and precise ever created for drumming, yet it was surely too complicated for students to read as a score. Therefore, its purpose was more as a reference work that preserved repertoire and provided a syllabus for structured learning.

We live in a literate age, and musicians recognise that their students no longer devote their waking hours to practising. Like other teachers, Afaq Hussain encouraged us all to write down the repertoire he taught so that it would not be forgotten. For me, it was especially important to capture two aspects in my own notebooks: rhythmic accuracy and precise fingering. Regarding the latter, for example, when faced with the phrase – keṛenaga tirakiṭa takataka tirakiṭa – I wanted to ensure that I notated the correct intended fingering from the dozen or so possible techniques for takataka, not to mention the varieties of keṛenaga, and I would also indicate that the two instances of tirakiṭa were played slightly differently.

Afaq Hussain kept his own notebooks safely stored in a locked cupboard. He sometimes consulted them. I think he recognised that repertoire does indeed disappear in the oral tradition – after all, there are many hundreds, if not thousands of pieces of music. His grandfather, Abid Hussain (1867-1936) was the first professor of tablā at the Bhatkhande Music College in Lucknow. He too notated tablā compositions, and I have hundreds of pages he wrote that were almost certainly intended to be published as a pedagogical text. However, he did not indicate precise rhythms or fingerings, and so interpreting his music is problematic, even for Afaq Hussain's son Ilmas Hussain with whom I combed through the material. A precise notation, then, does have value, but only alongside an oral tradition that can add the necessary layers of information that can bring the music to life.

– In your recent research on numerous Indo-Persian texts from the 18th and 19th centuries, you highlight the evolution of the representation of musical metre in India. This research illustrates the importance of the historical approach and fully demonstrates the mechanisms of the evolution of cultural facts. What concepts do you use to describe these phenomena?

An important facet of our anthropological training was learning to function in the language of those we engaged with in our research, not merely to manage life on a day-to-day basis but rather to have access to concepts that are meaningful within the culture studied. Two terms are significant in this regard, one whose importance is, I think, overstated, the other understated. Firstly, gharānā, which from its first appearance in the 1860s originally meant “family” but which over time has come to encompass anyone who believes they share some elements of technique, style, or repertoire with an apical figure of the past. Secondly, silsila, a term common in Sufism which means chain, connection, or succession, has specific relevance to a direct teaching lineage. It is this more precise silsila that I believe holds the key to the transmission of musical culture, and yet the paradox is that the chain carries within it an implicit directive to explore one's creative individuality. That is why, for example, when one examines, say, the lineage of Delhi tablā players from the mid 19th century onwards, one finds major differences in technique, style, and repertoire from generation to generation. The same is true for my teacher Afaq Hussain, whose playing differed greatly from that of his father and teacher Wajid Hussain. Each individual inherits some musical essence in the silsila, for sure, but they must engage with and operate in an ever-changing world where artistic survival requires adaptation. It is therefore vitally important when studying any musical era to gather as much information about the socio-cultural milieu as possible.

As I have shown above, it is imperative to engage with native concepts, and to explain and use them without recourse to translation. Another prime example is tāla, which most commonly gets translated as metre or metric cycle. And yet there is a fundamental difference. Metre is implicit: it is a pattern that is abstracted from the surface rhythms of a piece, and consists of an underlying pulse that is organized into a recurring hierarchical sequence of strong and weak beats. On the other hand, tāla is explicit: it is a recurring pattern of non-hierarchical beats manifested as hand gestures consisting of claps, silent waves, and finger counts, or as a relatively fixed sequence of drum strokes. To use metre in the Indian context is therefore misleading, and I therefore encourage the use of tāla with an accompanying explanation but without translation.

– You are currently working on a book about 18th and 19th century sources. What is your goal?

My goal is to trace the origins and evolution of the tāla system currently in use in Hindustani music by gathering as much information as possible from contemporary sources beginning in the late 17th century through to the early 20th century and the era of recorded sound. The problem is that the available information is fragmentary and often couched in obscure language: the task is akin to doing a jigsaw puzzle where most of the pieces are missing. Moreover, the pieces one does find are not necessarily directly connected, and so the task might be better described as working with two or more puzzles. In brief, through careful analysis, inference, and some guesswork, I believe that there was a convergence of rhythmic systems in the 18th century that gave rise to the tāla system of today.

The musical practices and social contexts of the communities of Kalāwants who sang dhrupad and Qawwāls who sang khayāl, tarāna, and qaul, along with the Ḍhāḍhī community that accompanied all these genres, are crucial to understanding how and why music – and rhythm in particular – evolved the way it did. Yet there are so many other important aspects to this story: the role of women instrumentalists in the private spaces of Mughal life in the 18th century, and their gradual disappearance in the 19th century; colonialism; the status and influence of ancient texts; printing technology and the dissemination of new pedagogical texts in the late 19th century – to name but a few.

– What are some of the interesting sources to consider in order to understand the evolution of practices and rhythmic representations of Hindustani music?

Northern India has always been open to cultural exchange, and this was especially true under the Mughals. It is imperative that we understand who travelled to the courts, from where, and what they played. It is equally important to understand the written materials available as well as the intellectual discourses of the time, for knowledge of music was crucial to Mughal etiquette. Thus, to know that the highly influential music treatise Kitāb al-adwār, by the 13th century theorist Safi al-Din al-Urmawi al-Baghdadi was widely available in India both in Arabic and Persian translation, and that copies were in the collection of Delhi nobles from the 17th century onwards, helps us to understand why Indian rhythm was explained using the principles of Arabic prosody in the late 18th century. I have argued that, as applied to music, Arabic prosody was a more powerful tool than the traditional methods of Sanskrit prosody, and thus it was more effective in describing the changes that were occurring in rhythmic thought and practice in that period.

– This ethno-historical research sometimes clashes with the beliefs of certain musicians and researchers, especially on questions of the age and “authenticity” of traditions. Do you think the younger generations are more inclined to accept the obvious facts of the complex nature of musical traditions made up of multiple contributions and in perpetual transformation?

Some are, but some are not. There has always been a small number of scholars in India who conduct valuable, evidence-based research on music. Yet it disappoints me to note there are many more that rely on the regurgitation and propagation of unfounded, unscholarly opinion. What perhaps surprises me most is the lack of rigorous scholarly training in Indian music colleges and the persistence of disproven or discredited ideas and information in spite of so much excellent published research to the contrary.

– Since the 1990s, one notices the strengthening of a Hindu nationalism within Indian society. Have you noted a particular impact on the world of Hindustani music and on research?

This is a complex and sensitive topic. Hindu nationalism is not new, far from it, and as I demonstrated in my book on Gurudev Patwardhan, it formed a significant part of the rationale for the life and work of Vishnu Digambar Paluskar in the early 20th century. As many scholars have pointed out, it had roots in colonialism, and developed as an anti-colonial movement focussed on Hindu identity politics. That narrative, based on invented notions of a glorious Hindu past, downplayed the contributions of Mughal culture and the great lineages of Muslim musicians (not to mention women), and Indian Muslim identity within the sphere of music has suffered a decline ever since. Scholars have taken note of this dynamic and have attempted to trace some of the counternarratives that have hitherto been ignored, such as Max Katz's excellent book Lineage of Loss (Wesleyan University Press, 2017) about an important family of Muslim scholar-musicians, the so-called Shāhjahānpūr-Lucknow gharānā. I suspect that a motivational force in much modern scholarship on music in India is the desire not to omit important cultural narratives but to animate them and frame them within the grand sweep of South Asia's history.

– Following on from Rebecca Stewart's work, you too have highlighted the complex interweaving of rhythmic and metric approaches in tablā playing by showing that it results from various cultural contributions which have followed one another over time. With the intensification of global cultural exchanges since the end of the 20th century, have you observed one or more evolving trends in tablā playing?

Since the inclusion of tablā in pop music in the 1960s, the exciting jazz fusion of John McLaughlin's group Shakti in the 1970s, and the ubiquity of tablā ever since in music of every kind, it seems only natural that tablā players the world over should explore and experiment with its magical sounds. Zakir Hussain has led the way in demonstrating the flexibility and adaptability of these drums, and the thrilling, visceral velocity of its rhythmic patterns. As for tablā within the context of Hindustani concert music, I have noticed that there are many who attempt to inject that same sense of excitement, enhanced increasingly, it seems, by amplification so loud that it distorts the sound and beats the audience's eardrums into submission. I would go so far as to say that this has unfortunately become the norm.

In this regard, I count myself as something of a purist who longs for a return to a practice where the tablā player maintains a subtle, understated yet supportive role, complements the material presented by the soloist, and is modest and not overpowering when invited to contribute a short flourish or cameo solo. By the same token, I crave a return to tablā solos that are packed with content rather than “sound effects.” By “content,” I mean traditional, characterful compositions featuring specialised techniques, whose composers are named and thus honoured. And yet it is painfully obvious that such “content” is not reaching many younger players these days.

Ethnomusicology

– As mentioned, your research highlights the importance of historical sources as well as the consideration of broader phenomena such as Orientalism or Nationalism in order to understand Indian musical practices in the present. At the same time, you are very attentive to the intense current transcultural phenomena and to the need to comprehend them. In the profession, the concept of “ethnomusicology” does not always achieve consensus. What is your position with regard to this name and the subject of this discipline at the start of the 21st century?

I have never been particularly comfortable with the label “ethnomusicology.” As John Blacking used to say, all music is “ethnic music,” and therefore there should be no distinction between studies of tablā, gamelan, or hip-hop and those of Bach, Beethoven, or Brahms. We all engage in a “discourse on music”: in other words, “musicology.” The advantage of terms like the “anthropology” or “sociology” of music is that they imply a broader slate of theoretical and methodological approaches that remind us that music is a social fact. Yet we must recognise that the purview of ethnomusicological studies has evolved, and nowadays far greater attention is paid to phenomena like noise or the mundane sounds of everyday life. Therefore – without wishing to sound too cynical – although in some quarters the term “sound studies” is treated with a degree of contempt, perhaps that very general term is the most honest and accurate definition of what we (all of us) do. However, I acknowledge that it would be a shame to reject the term “music” altogether, and so I could imagine ethnomusicology, musicology, and music theory coming together under the rubric “music and sound studies.”

Teaching

– After a short period in Belfast, you taught in Toronto. Can you tell us about your teaching experience?

Yes, Toronto is a wonderful city, and by most accounts it is the most multi-cultural city on this planet. It offers a very rich and stimulating musical environment.

Miecyzslaw Kolinski taught at the University of Toronto from 1966 until 1978. His ethnomusicological interests were shaped by his training under Hornbostel and Sachs, and by the worldview shared by so many of the early giants of our discipline. He published on the scientific basis of harmony and melody, and developed methods for cross-cultural analysis – an approach emphatically rejected in my own training with John Blacking who argued vehemently for cultural relativism, much as it was at odds with Tim Rice's training at the University of Washington. Tim was hired in 1974 and left for UCLA in 1987. Like me during my early days, Tim struggled to persuade colleagues of the importance of the ethnomusicological approach and the need to treat our discipline with the respect it deserved and the resources it required. We both fought hard. Tim introduced a program that came to be known under my watch as the World Music Ensembles, and I acquired a Balinese gamelan in 1993, which was taught by my wife, ethnomusicologist Dr Annette Sanger, formerly a colleague of John Blacking. Moreover, both Tim and I succeeded in drawing ethnomusicology classes further into the core of the curriculum to ensure that all music students, whatever their interests, were exposed to our approach and understood the value and importance of a socially-grounded view of all music. One initiative I created was a year-long introductory course called Music as Culture which for a few years I co-taught with a musicology colleague: we alternated our presentations, illustrating and cross-referencing our material and observations from the Western canon and the vast world of music beyond. Later incarnations of this course included our flagship Introduction to Music & Society. Essentially modular in approach, the chosen themes shifted and adapted over time to reflect more contemporary concerns, including music and identity, religious experience, migration, gender, healing, and sound studies.

I devised and taught a variety of courses during my time: Hindustani music; Music & Islam; Theory & Method in Ethnomusicology; The Beatles; Anthropology of Music; Fieldwork; Music, Colonialism & Postcolonialism; Rhythm & Metre in Cross-Cultural Perspective; Transcription, Notation & Analysis, etc. I worked with the South Asian community in Toronto to put on concerts by vocalist Pandit Jasraj that drew sponsorship that generated healthy scholarships for students studying Hindustani music. I helped institute an Artist-in-Residence program, inviting musicians from all over the world to spend a term with us teaching and performing. I helped to overhaul our musicology-oriented graduate programmes and introduced an MA and PhD in ethnomusicology. But perhaps the two achievements of which I am most proud are firstly the many wonderful doctoral students I mentored, many of whom have themselves gone on pursue to careers in academia, and secondly my success in expanding our representation from a single faculty position to four full-time positions in ethnomusicology.

– What is your position within the Lucknow gharānā?

I have greatly enjoyed learning and playing tablā in my life, and I consider myself extremely fortunate to have had such a close and productive association with one of the most remarkable tablā players in history: Afaq Hussain. I am blessed with a good memory and therefore still have in my head a vast repertoire of wonderful compositions dating all the way back to the early members of the Lucknow lineage who flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. I am particularly interested in technique, and have spent a good deal of time studying the mechanics of playing. However, I am first and foremost a scholar, and in practical matters I have no illusions about being anything more than a tablā hobbyist. Indeed, my interest in playing has provided me with extraordinary insights into the instrument and its history.

As for my place or role within the Lucknow gharānā, I would say two things. Firstly, I continue to be part of the exchange of ideas and repertoire with my peers alongside whom I studied tablā and who now are, like me, senior figures within the silsila, the direct teaching lineage of Afaq Hussain. I am considered by them to be knowledgeable: an authority, if you will. On occasions I am asked if I remember a rare composition over which there has been some debate, and sometimes I introduce into our dialogue information and questions arising from my research that spark a lively interest. For example, Afaq Hussain's son Ilmas Hussain and I have been working together to resurrect the notebooks of his great-grandfather Abid Hussain, and place them in the context not only of his tradition but also of the early years of Lucknow's Bhatkhande College where Abid Hussain served as the first professor of tablā in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Secondly, I believe that my work has brought greater attention to the Lucknow lineage. When I arrived at Afaq Hussain's doorstep in January 1981 he was frankly at a low ebb in his life – psychologically and financially – and much about the future was uncertain. Other foreign students followed my lead and joined an ever-growing number of Indian disciples who came to learn. My book, The Tabla of Lucknow, as well as other facets of my research helped to bring national and international attention to Afaq Hussain, his son Ilmas, and their entire tradition.

When I came to Toronto I made a decision not to teach tablā outside of my duties at the University of Toronto, since I did not wish to risk depriving local tablā players (of whom there were several very good ones) of the opportunity to earn income. Within the university itself, I did run occasional workshops and courses for students, plus individual lessons, and some of them (particularly percussionists) became quite competent players.

List of publications

Books

2006 Gurudev’s Drumming Legacy: Music, Theory and Nationalism in the Mrdang aur Tabla Vadanpaddhati of Gurudev Patwardhan. Aldershot: Ashgate (SOAS Musicology Series).

2005 The Tabla of Lucknow: A Cultural Analysis of a Musical Tradition. New Delhi: Manohar (New edition with new preface).

1988 The Tabla of Lucknow: A Cultural Analysis of a Musical Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (Cambridge Studies in Ethnomusicology).

Edited books

2013 with Frank Kouwenhoven, Music, Dance and the Art of Seduction. Delft: Eburon Academic Publishers.

Edited journals

1994-1996 Bansuri, volumes 11-13 (A yearly journal devoted to the music and dance of India, published by Raga Mala Performing Arts of Canada).

Articles, chapters in books

Forthcoming “Weighing ‘The Assets of Pleasure’: Interpreting the Theory and Practice of Rhythm and Drumming in the Sarmāya-i ‘Ishrat, a Pivotal 19th Century Text” in Katherine Schofield, ed.: Hindustani Music Between Empires: Alternative Histories, 1748-1887. Publisher TBA.

Forthcoming “An Extremely Nice, Fine and Unique Drum: A Reading of Late Mughal and Early Colonial Texts and Images on Hindustani Rhythm and Drumming” in Katherine Schofield, Julia Byl et David Lunn, eds: Paracolonial Soundworlds: Music and Colonial Transitions in South and Southeast Asia. Publisher TBA.

2021 “Ethnomusicology at the Faculty of Music, University of Toronto.” MUSICultures (Journal of the Canadian Society for Traditional Music): Vol.48.

2020 “Rhythmic Thought and Practice in the Indian Subcontinent” in Russell Hartenberger & Ryan McClelland, eds: The Cambridge Companion to Rhythm. Cambridge University Press: 241-60.

2019 “Mapping a Rhythmic Revolution Through Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Sources on Rhythm and Drumming in North India” in Wolf, Richard K., Stephen Blum, & Christopher Hasty, eds: Thought and Play in Musical Rhythm: Asian, African, and Euro-American Perspectives. Oxford University Press: 253-72.

2013 “Introduction” in Frank Kouwenhoven & James Kippen, eds: Music, Dance and the Art of Seduction. Delft: Eburon Academic Publishers: i-xix.

2010 “The History of Tabla” in Joep Bor, Françoise ‘Nalini’ Delvoye, Jane Harvey and Emmie te Nijenhuis, eds: Hindustani Music, Thirteenth to Twentieth Centuries. New Delhi: Manohar: 459-78.

2008 “Working with the Masters” in Gregory Barz and Timothy Cooley, eds:Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology (2nd revised edition). Oxford University Press: 125–40.

2007 “The Tal Paddhati of 1888: An Early Source for Tabla.” Journal of The Indian Musicological Society, 38: 151–239.

2003 “Le rythme: Vitalité de l'Inde.” Gloire des princes, louange des dieux: Patrimoine musical de l'Hindoustan du XIVe au XXe siècle. Paris: Cité de la musique et Réunion des Musées Nationaux 2003:152–73.

2002 “Wajid Revisited: A Reassessment of Robert Gottlieb’s Tabla Study, and a new Transcription of the Solo of Wajid Hussain Khan of Lucknow.” Asian Music, 33, 2: 111–74.

2001 “Folk Grooves and Tabla Tals.” ECHO: a music-centered journal. III: 1 (Spring 2001).

2000 “Hindustani Tala.” Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 5, South Asia: The Indian Subcontinent. New York: Garland Publishing: 110–37.

1997 “The Musical Evolution of Lucknow” in Violette Graff, dir., Lucknow: Memories of a City. New Delhi: Oxford University Press: 181–95.

1996 “A la recherche du temps musical.” Temporalistes, 34: 11-22

1994 “Computers, Composition, and the Challenge of ‘New Music’ in Modern India.” Leonardo Music Journal, 4: 79–84. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00143124

1992 “Tabla Drumming and the Human-Computer Interaction.” The World of Music, 34, 3: 72–98.

1992 “Music and the Computer: Some Anthropological Considerations.” Interface, 21, 3-4: 257–62.

1992 “Where Does The End Begin ? Problems in Musico-Cognitive Modelling.” Minds & Machines, 2, 4: 329–44.

1992 “Identifying Improvisation Schemata with QAVAID” in Walter B. Hewlett & Eleanor Selfridge-Field, eds: Computing in Musicology: An International Directory of Applications, Volume 8. Center for Computer Assisted Research in the Humanities:115–19.

1992 “Bol Processor Grammars” in M. Balaban, K. Ebcioglu, & O. Laske, eds: Understanding AI with Music, AAAI Press: 367–400. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00256386

1992 with Bernard Bel “Modelling Music with Grammars: Formal Language Representation in the Bol Processor” in A. Marsden & A. Pople, eds: Computer Representations and Models in Music. London, Academic Press: 207–38. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00004506

1991 with Bernard Bel “From Word-Processing to Automatic Knowledge Acquisition: A Pragmatic Application for Computers in Experimental Ethnomusicology” in Ian Lancashire, ed.: Research in Humanities Computing I: Papers from the 1989 ACH-ALLC Conference, Oxford University Press: 238–53.

1990 “Music and the Computer: Some Anthropological Considerations” in B. Vecchione & B. Bel, eds: Le Fait Musical – Sciences, Technologies, Pratiques, préfiguration des actes du colloque Musique et Assistance Informatique, CRSM-MIM, Marseille, France, 3-6 Octobre: 41–50.

1990 “In Memoriam: Afaq Husain (1930-1990).” Ethnomusicology 34, 3: 429–30.

1990 “In Memoriam: John Blacking (1928-1990).” Ethnomusicology 34, 2: 263–6.

1989 “Changes in the Social Status of Tabla Players.” Journal of the Indian Musicological Society, 20, 1 & 2: 37–46.

1989 “Can a Computer Help Resolve the Problem of Ethnographic Description?” Anthropological Quarterly, 62, 3: 131–44. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00275429

1989 with Bernard Bel “The Identification and Modelling of a Percussion ‘Language’, and the Emergence of Musical Concepts in a Machine-Learning Experimental Set-Up.” Computers and the Humanities, 23, 3: 199–214. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00004505

1988 with Bernard Bel “Un modèle d’inférence grammaticale appliquée à l’apprentissage à partir d’exemples musicaux.” Neurosciences et Sciences de l’Ingénieur, 4e Journées CIRM, Luminy, 3–6 Mai 1988.

1987 “An Ethnomusicological Approach to the Analysis of Musical Cognition.” Music Perception 5, 2: 173–95.

1987 with Annette Sanger “Applied Ethnomusicology: the Use of Balinese Gamelan in Recreational and Educational Music Therapy.” British Journal of Music Education 4, 1: 5–16.

1986 with Annette Sanger “Applied Ethnomusicology: the Use of Balinese Gamelan in Music Therapy.” International Council for Traditional Music (UK Chapter) Bulletin, 15: 25–28.

1986 “Computational Techniques in Musical Analysis.” Bulletin of Information on Computing and Anthropology (University of Kent at Canterbury), 4: 1–5.

1985 “The Dialectical Approach: a Methodology for the Analysis of Tabla Music.” International Council for Traditional Music (UK Chapter) Bulletin, 12: 4–12.

1984 “Linguistic Study of Rhythm: Computer Models of Tabla Language.” International Society for Traditional Arts Research Newsletter, 2: 28–33.

1984 “Listen Out for the Tabla.” International Society for Traditional Arts Research Newsletter, 1: 13–14.

Reviews

2012 Elliott, Robin and Gordon E. Smith, eds: Music Traditions, Cultures and Contexts, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, in “Letters in Canada 2010”, University of Toronto Quarterly, 81: 3:779–80.

2006 McNeil, Adrian Inventing the Sarod: A Cultural History. Calcutta: Seagull Press, 2004. Yearbook for Traditional Music, 38: 133–35.

1999 Myers, Helen, Music of Hindu Trinidad: Songs from the India Diaspora. Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998. Notes: 427–29.

1999 Marshall, Wolf, The Beatles Bass. Hal Leonard Corporation, 1998. Beatlology, 5.

1997 Widdess, Richard, The Ragas of Early Indian Music: Music, Modes, Melodies, and Musical Notations from the Gupta Period to c.1250. Oxford Monographs on Music. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 117, 3: 587.

1994 Rowell, Lewis, Music and Musical Thought in Early India. Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology, edited by Philip V. Bohlman and Bruno Nettl. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1992. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 114, 2: 313.

1992 CD: review “Bengal: chants des ‘fous’”, par Georges Luneau & Bhaskar Bhattacharyya, and “Inde du sud: musiques rituelles et théâtre du Kerala”, par Pribislav Pitoëff. Asian Music 23, 2:181–84.

1992 Witmer, Robert, ed.: “Ethnomusicology in Canada: Proceedings of the First Conference on Ethnomusicology in Canada.” (CanMus Documents, 5) Toronto, Institute for Canadian Music, 1990. Yearbook for Traditional Music, 24: 170–71.

1992 Neuman, Daniel M. The Life of Music in North India: The Organization of an Artistic Tradition. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1990. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 112, 1: 171.

1988 Qureshi, Regula Burckhardt. Sufi Music of India and Pakistan: Sound, Context and Meaning in the Qawwali. Cambridge Studies in Ethnomusicology. Cambridge: CUP, 1986. International Council for Traditional Music (UK Chapter) Bulletin, 20: 40–45.

1986 Wade, Bonnie C. Khyal: Creativity within North India’s Classical Music Tradition. Cambridge Studies in Ethnomusicology. Cambridge: CUP. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society: 144–46.

Recordings

1999 Honouring Pandit Jasraj at Convocation Hall, University of Toronto. 2 CD set. Foundation for the Indian Performing Arts, FIPA002.

1995 Pandit Jasraj Live at the University of Toronto. 2 CD set. Foundation for the Indian Performing Arts, FIPA001.

Liner notes

2009 Mohan Shyam Sharma (pakhavaj): Solos in Chautal and Dhammar. India Archive Music CD, New York.

2007 Anand Badamikar (tabla): Tabla Solo in Tintal. India Archive Music (IAM•CD 1084), New York.

2002 Pandit Shankar Ghosh: Tabla Solos in Nasruk Tal and Tintal. CD, India Archive Recordings (IAM•CD1054), New York.

2001 Shujaat Khan, Sitar: Raga Bilaskhani Todi & Raga Bhairavi. CD, India Archive Recordings (IAM•CD1046), New York.

1998 Pandit Bhai Gaitonde: Tabla Solo in Tintal. CD, India Archive Recordings (IAM•CD1034), New York.

1995 Ustad Amjad Ali Khan: Rag Bhimpalasi & Rag “Tribute to America”. CD, India Archive Recordings (IAM•CD1019), New York.

1994 Ustad Nizamuddin Khan: Tabla Solo in Tintal. CD, India Archive Recordings (IAM•CD1014), New York.

1992 Rag Bageshri & Rag Zila Kafi, played by Tejendra Narayan Majumdar (sarod) and Pandit Kumar Bose (tabla). CD, India Archive Recordings (IAM•CD 1008), New York.

Obituaries

1990 “In Memoriam: Afaq Husain (1930-1990).” Ethnomusicology 34, 3: 429–30.

1990 “In Memoriam: John Blacking (1928-1990).” Ethnomusicology 34, 2: 263–6.

➡ A new version of Bol Processor compliant with various systems (MacOS, Windows, Linux…) is under development. We invite software designers to join the team and contribute to the development of the core application and its client applications. Please join the BP open discussion forum and/or the BP developers list to stay in touch with work progress and discussions of related theoretical issues.