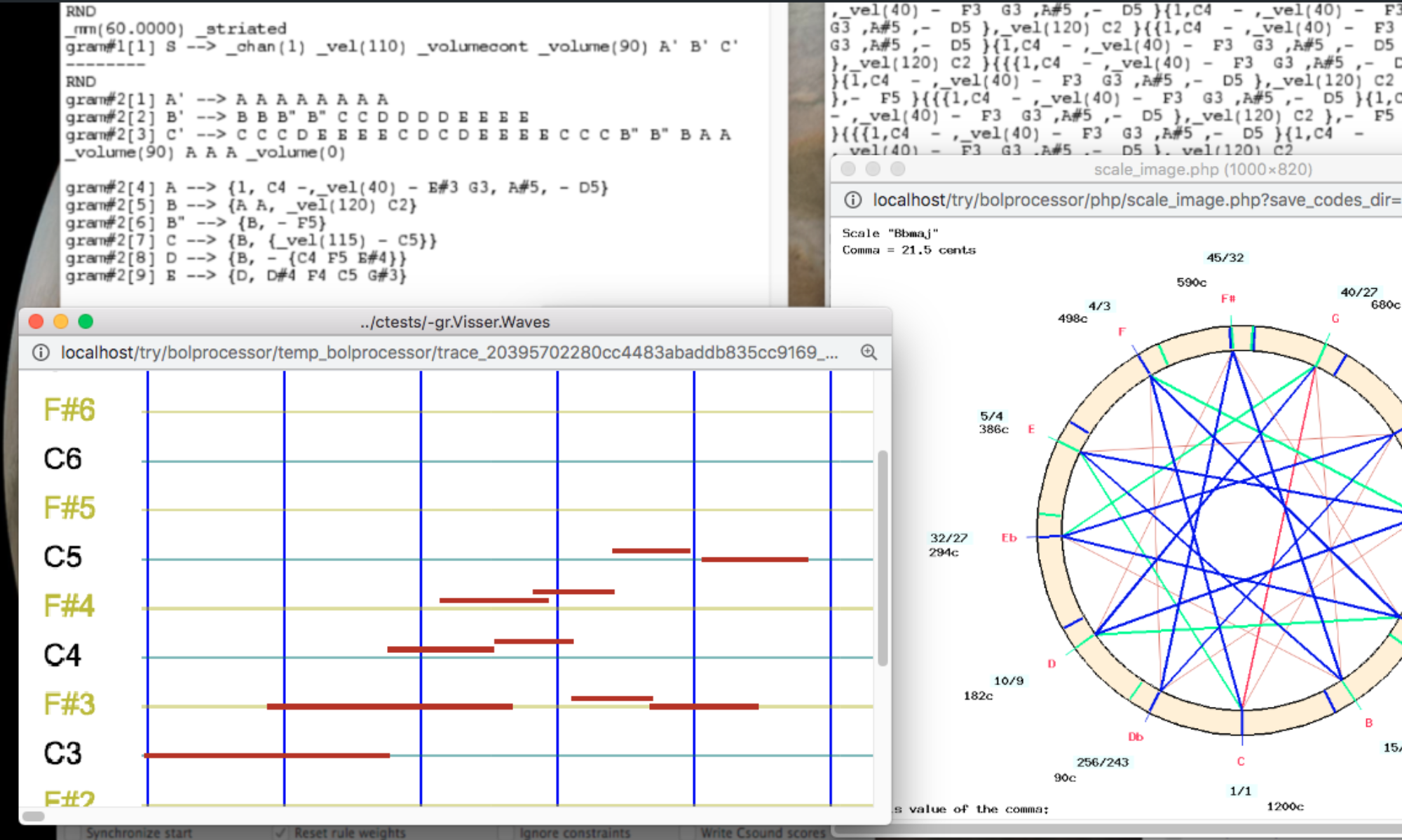

The following are Bol Processor + Csound interpretations of J.-S. Bach's Prelude 1 in C major (1722) and François Couperin's Les Ombres Errantes (1730) — both near the end of the Baroque period — using temperament scales (Asselin 2000). The names and tuning procedures follow Asselin's instructions (p. 67-126). Images of the scales have been created using the Bol Processor.

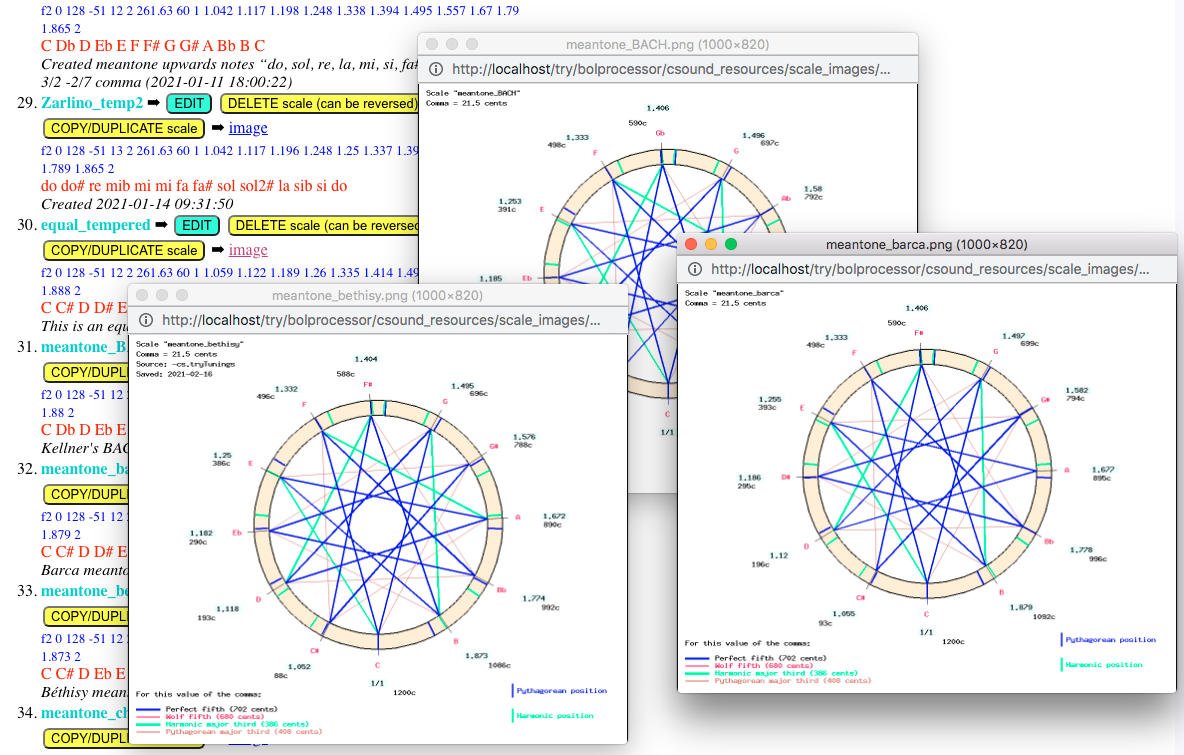

The construction of these scales with the Bol Processor is explained in detail on the Microtonality page. The complete set of scale images is available on this page.

➡ We hope to be able to release better sound demos upon receipt of a set of well-designed C-sound instruments. ("orc" files). My apologies to harpsichord players, tuners and designers!

Bach's Prelude 1 in C major (1722)

This is the first prelude in a series called Well-Tempered Clavier by Johann Sebastian Bach. Well-tempered, ok… But which temperament?

Let us begin by listening to the piece in equal temperament, the popular tuning of instruments in the electronic age. Unlearned musicians believe that "well-tempered" is the equivalent of "equal-tempered."

➡ Don't hesitate to click on the "Image" links to see circular graphical representations of scale intervals highlighting consonance and dissonance.

The following are traditional temperaments, each of which was designed at a particular time to meet the specific requirements of the musical repertoire en vogue (Asselin 2000 p. 139-180).

The previous example was Zarlino's temperament, not to be confused with the popular "natural scale" of Zarlino, an example of just intonation:

J.S. Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier (BWV 846–893) is a collection of two sets of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys, dated 1722. To judge the validity of a tuning scheme it would be necessary to listen to all the pieces. Readers impatient to know more may be interested in a "computational" approach to the subject, read Bach well-tempered tonal analysis and listen to the results on the page The Well-tempered Clavier.

Fortunately, there are historical clues as to the optimal choice: Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg received information from Bach's sons and pupils and Johann Kirnberger, one of these pupils, designed tunings that he claimed represented his master's idea of "well-tempered".

On the page Tonal analysis of musical items we show that the analysis of tonal intervals tends to suggest the choice of Kirnberger III rather than Kirnberger II. However, the temperament devised by the French physician Joseph Sauveur in 1701 also seemed to fit better in terms of melodic intervals — and indeed it sounds beautiful… This, in turn, can be challenged by the systematic matching of all the works in books I and II with the tuning schemes implemented on the Bol Processor — see page Bach well-tempered tonal analysis.

François Couperin's Les Ombres Errantes (1730)

Again, my apologies to harpsichord players, tuners and manufacturers!

This piece is from François Couperin's Quatrième livre published in 1730 ➡ read the full score (Creative Commons licence CC0 1.0 Universal). We used it to illustrate the interpretation of mordents when importing MusicXML files.

First, listen to an (excellent) interpretation of this work by the harpsichord player Iddo Bar-Shaï (source: https://youtu.be/DCwkMSTFV_E).

Despite its artistic quality, this performance has some dissonant effects, which are partly masked by the abundance of melodic ornamentation: mordents, trills, etc. Such a departure from the theme of the 'Ombres errantes' cannot be attributed to either the composer or the performer. It is therefore legitimate to question the tuning of the instrument. To do this, we must focus our attention on tonality, even if the sound synthesis seems artificial to listeners whose attention is focused on temporality, ornamentation and sound quality.

As some of the following temperaments were invented (or documented?) after 1730, it is unlikely that the composer used them. Let's try them all anyway, and find the winner!

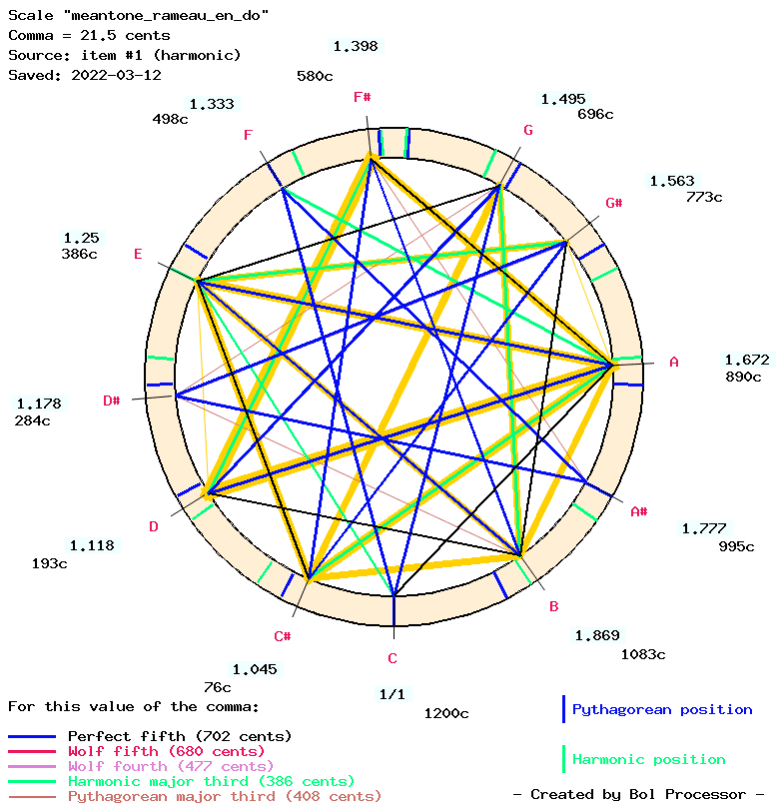

(see full image)

The best temperament for this piece might be Rameau en sib, which was devised by Couperin's contemporary Jean-Philippe Rameau for musical works with flats in the key signature (Asselin, 2000 p. 149) — such as the present one. See the Tonal analysis of musical items page for a description of a systematic (automated) analysis that confirms this choice.

We might end up with listening to François Couperin's Le Petit Rien (Ordre 14e de clavecin in D major, 1722), which has two sharps in the key signature, suggesting the use of a Rameau en do temperament.

This choice is also confirmed by the method described on the page Tonal analysis of musical items.

Source: MusicXML score by Yvan43

Bernard Bel — 2022

Work in progress

Chapter VIII of Pierre-Yves Asselin's book (2000 p. 139-180) contains examples of musical works that illustrate the relevance of specific temperaments. As the scores of many baroque and classical masterpieces are available in the digital format MusicXML, we hope to use Bol Processor's Importing MusicXML scores to transcode them and play these fragments with the suggested temperaments.

Despite the limitations of comparing temperaments on only two musical examples, the aim of this page is to illustrate the notion of "perfection" in sets of tonal intervals — and in music in general. Read the discussion: Just intonation: a general framework. If nothing else, we hope to convince the reader that "equal temperament" is not the "perfect" solution!

Musicians interested in continuing this research and related development can use the beta version of the Bol Processor BP3 to process musical works and create new tuning procedures. Follow the instructions on the Bol Processor ‘BP3’ and its PHP interface page to install BP3 and learn its basic operation. Download and install Csound from its distribution page.

References

Asselin, P.-Y. Musique et tempérament. Paris, 1985, republished in 2000: Jobert. Soon available in English.