👉 For geeks only!

This page is about the polymetric notation used in the Bol Processor project and, most likely, other software environments. This advanced tool is used to represent the time structure of events, which can be simple notes, sound-objects, or more generally time-objects that can be instantiated as video fragments, sequences of robotic actions, and so on.

In a polymetric structure, rests (or 'silences') are represented by integer ratios (their symbolic duration), for example ‘6’ for "six beats" or '4 2/3' for "four and two third beats". Small integers can be replaced with hyphens, for example '---' for '3'.

In some (but not all) polymetric structures, rests with explicit durations can be replaced with undetermined rests (notated '…' or '_rest'), the value of which is calculated by a (deterministic) algorithm in the console (file 'polymetric.c'). This is an important feature because it enables the notation to be simplified without compromising the accuracy of the time. Take a look at Charles Ames' example, for instance.

A polymetric structure containing at least an undetermined rest is called 'minimised" for this reason. Examples of minimised structures are found on the Polymetric structures page.

The topic of this page is about 'reverting' the algorithm that assigns explicit durations to undetermined rests in the Bol Processor console. Geeks will find this algorithm in the 'polymetric.c' file, and they can set the 'trace_und' variable to '1' to trace its operation.

Examples of minimisation

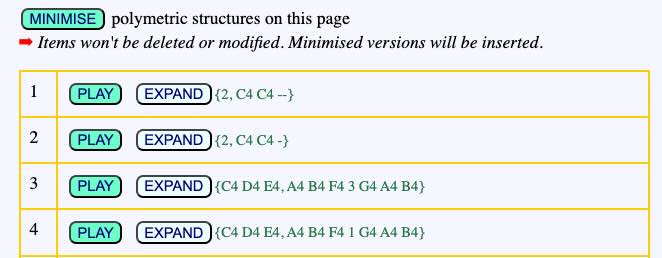

All examples are found in the "-da.tryMinimise" data file (distributed from the 3.3.6 version). Click the MINIMISE button to minimise all (eligible) polymetric expressions on the page.

Only polymetric expressions between curled braces { } are processed.

The first example {2, C4 C4 --} will be minimised as {2, C4 C4 …} whereas the second example {2, C4 C4 -} is not eligible. The reason is that {2, C4 C4 …} is always instantiated as {2, C4 C4 --} (or {2, C4 C4 2}) and there is no minimised version of {2, C4 C4 -}.

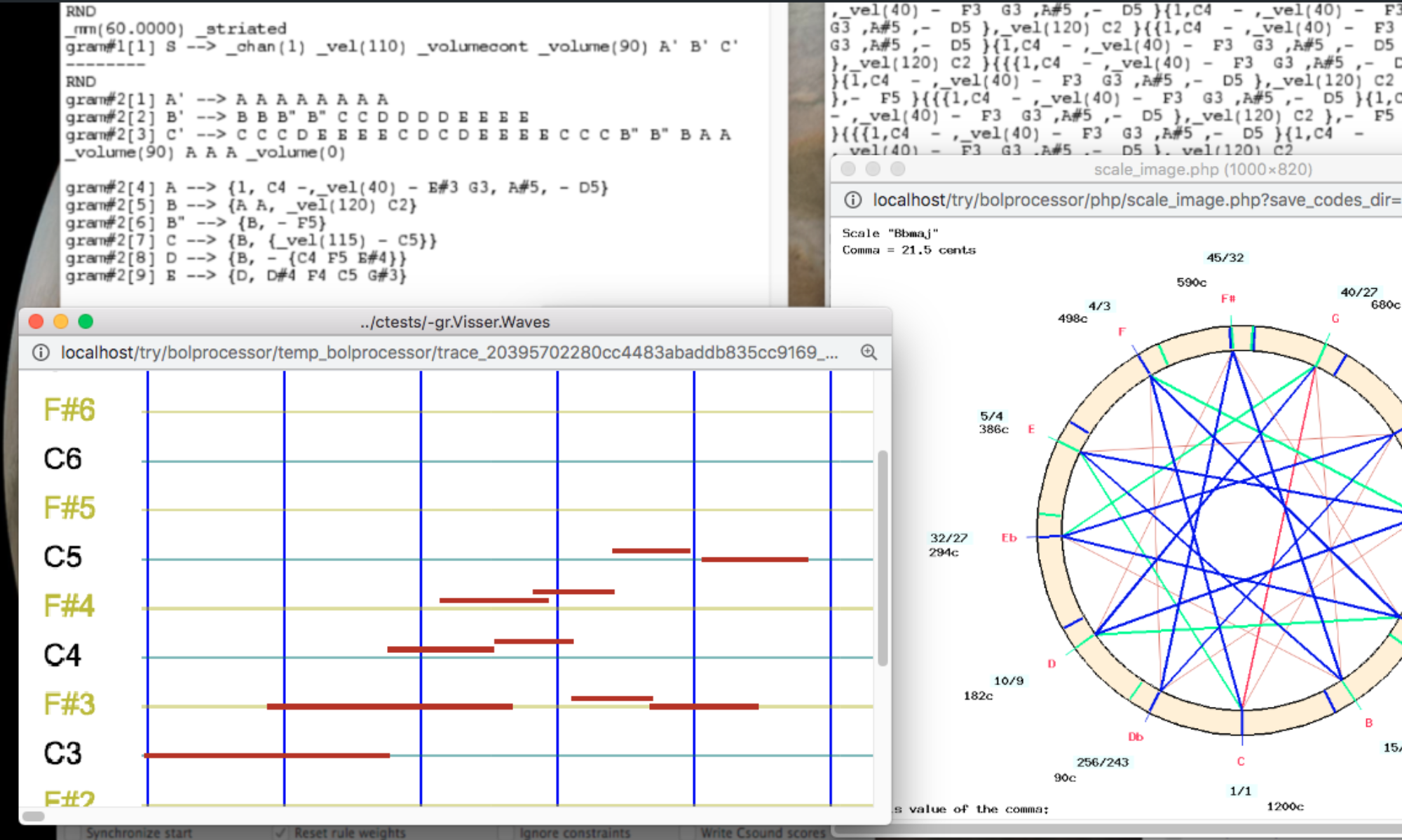

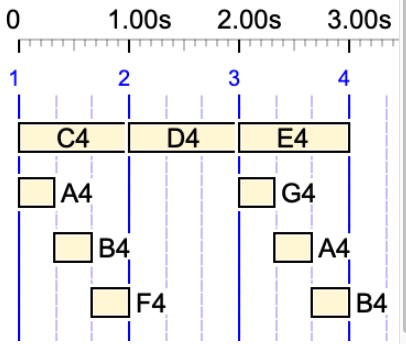

The third example {C4 D4 E4, A4 B4 F4 3 G4 A4 B4} is minimised as {C4 D4 E4, A4 B4 F4 …G4 A4 B4}. Both versions yield the following time structure:

For this demo, we use simple notes with arbitrary pitches in English notation, as we are only focusing on the time structures.

The following examples are not eligible for a minimisation:

{C4 D4 E4, A4 B4 F4 1 G4 A4 B4}

{C4 D4 E4, A4 B4 F4 2 G4 A4 B4}

{C4 D4 E4, A4 B4 F4 4 G4 A4 B4}

It is not easy to guess which duration of the rest — 1, 2, 3, 4 beats? — makes it eligible for being undetermined. The correct value can be found by clicking the EXPAND button to the right of {C4 D4 E4, A4 B4 F4 … G4 A4 B4}. The first line of the result is the expanded polymetric expression:

/1 {*1/1 C4 D4 E4,*1/3 A4 B4 F4 - _ _ G4 A4 B4}

The '- _ _ ' sequence is a rest of duration 3 beats. The symbol '-' represents a rest of one beat. This is followed by two prolongations, '_'.

Note that the "expanded polymetric expression" displays absolute tempo markers, such as '*1/3', to represent the structure, rather than relative markers, such as '__tempo(1/3)'. This representation can be used for data, as was the case in early versions of the Bol Processor.

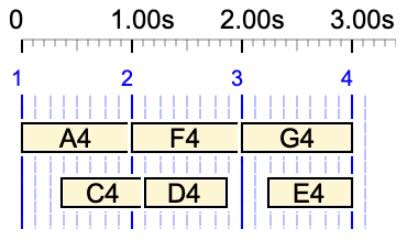

Indeed, in this simple example, the duration was visible on the graph. However, it becomes increasingly difficult to measure when rhythmic structures become more complicated. For example, {A4 F4 G4, … C4 D4 … E4} is expanded as:

/1 {*1/1 A4 F4 G4, *3/8 - *3/4 C4 D4 *3/8 - *3/4 E4}

It is not easy to figure out that '*3/8 -' is a silence at twice the speed of '*3/4 C4', therefore its (relative) duration is 1/2 and the structure is equivalent to {A4 F4 G4, 1/2 C4 D4 1/2 E4}.

The process is more complex for fields of the polymetric structure that contain at least two rests with different durations. For example:

{C3 D3 E3, A5 5/4 B5 5/2 C5 5/4 D5}

The algorithm generates a table of equivalent rests in chains, such as two 5/4 rests and one 5/2 rest. The table is sorted down on the number of rests in each chain, which yields:

5/4 5/4

5/2

Then, each chain is considered as a potential solution to the undetermined rest(s). The first one that meets the conditions provides the solution. Here, it is "5/4 5/4", which yields:

{C3 D3 E3, A5 … B5 5/2 C5 … D5}

In this example, {C3 D3 E3, A5 5/4 B5 … C5 5/4 D5} is another solution.

If several chains contain the same number of units, the first acceptable one is given as the solution and the (deterministic) algorithm ends. However, other chains of maximum length might also meet the conditions. This means that the minimisation algorithm does not provide all solutions, but at least it does provide one which has the maximum number of undetermined rests.

Tracing the minimisation

The algorithm for minimising polymetric structures is more complicated to design than the one for assigning explicit durations to undetermined rests. As per this writing, it does not cover all cases. Updated versions will be implemented in the interface file 'data.php'.

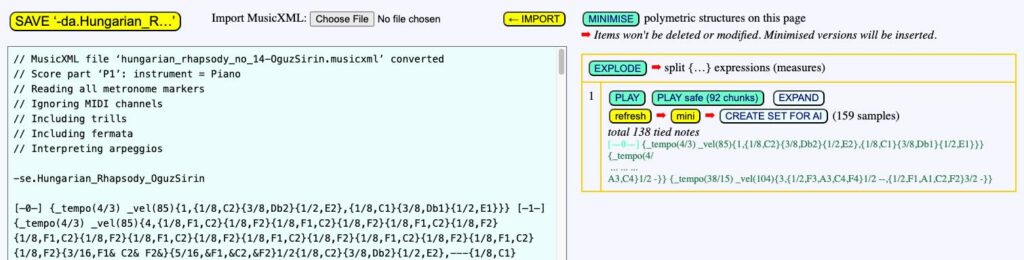

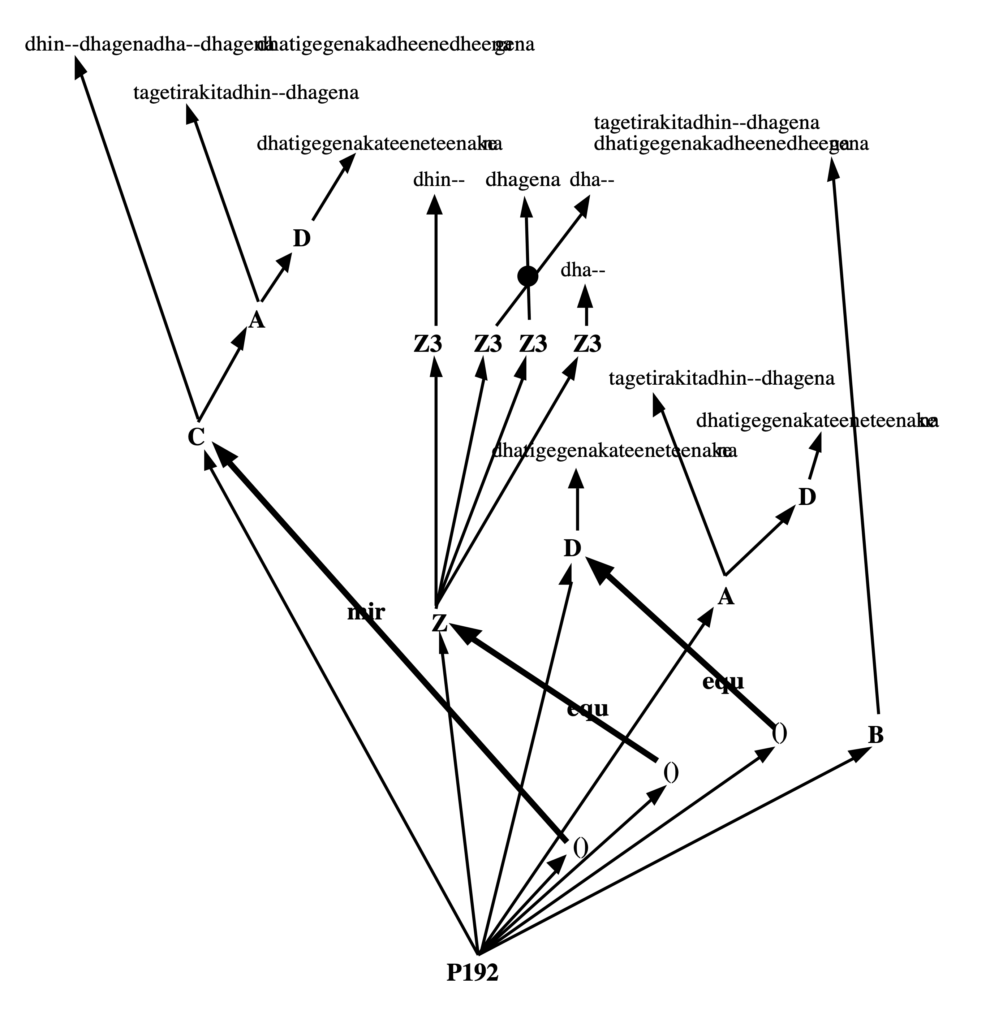

If you need to follow the process while looking at the code, open the settings file and enter the item number at the bottom of the form. In this example, we have chosen to trace the minimisation of item #30.

Don't forget to save the settings and save again the Data page. Now, click the MINIMISE button. You will get a trace that looks like this:

👉 { C3 D3 E3 , A5 5/4 B5 5/2 C5 5/4 D5 }

field #0 = 3/1 sounds, 3/1 beats, tempo = 1/1

field #1 = 9/1 sounds, 9/1 beats, tempo = 1/1

ref field = 0, duration = 3/1 beats

sounds = 9/1

TRYING field #1, "A5 5/4 B5 5/2 C5 5/4 D5 "

—> ref_field = 0, token = "5/4", number_rests = 2, duration = 5/2

➡ beats (3/1) - sounds (9/1) + rest duration (5/2) = xp/xq = -7/2, number_rests = 2

case 1 —> beats[ref_field] = 3/1, sounds[field] = 13/4

pmax/qmax = 12/4, lcm = 4, psounds/qsounds = 13/4

mgap = 1, x = 1.0833333333333, p_therest (before adjust) = 5.5

p_therest (after adjust) = 5, q_therest = 4

[field #1 -> rest = 5/4]

GOT IT: "A5 _rest B5 5/2 C5 _rest D5" —> count_this = 2

Result = {C3 D3 E3 , A5 _rest B5 5/2 C5 _rest D5}

(This trace will differ in subsequent versions.)

.🛠 Work in progress .…. to be continued .….…